In their book “The Right Game, Use Game Theory to Shape Strategy,” Adam Brandenburger and Barry J. Nalebuff make a good demonstration of how Game Theory applies to Business Strategy.

The first relevant thing is that they do not talk about improving our way of playing the game but choosing the suitable game to play. Traditionally we think about current situations as given and not in ways in which we can influence the rules of the game.

John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern first introduced the Game Theory in 1944, publishing their book “Theory of Games and Economic Behaviour.” Their work provided a systematic way to understand players’ behavior in the same environment.

They defined two types of games:

- Rule-based games: Where there are in place contracts or agreements to follow.

- Freewheeling games: Where there are no external limitations.

In all businesses, we have a mix of both. Knowing which one is the predominant one is essential, as different principles drive them.

- For rule-based games: “To every action, there is a reaction.”

- They require to guess other players’ reactions to the company’s actions based on their self-interest and the rules in place.

- For freewheeling games: “You cannot take away from the game more than you bring it.”

- Like in a perfectly competitive market, everybody will take what he can contribute to the rest of the players.

In order to understand these processes better, Brandenburg and Nalebluff bring examples of different situations in which the theory of games was applied successfully.

From lose-lose to win-win

First, they tell us how in the automobile industry of the early 1990s, General Motors was able to change a lose-lose game. The different companies were competing basically on price to a win-win, where all of them managed to increase their prices indirectly.

GM did this by issuing a new credit card that allowed card-holders to apply 5% of their charges towards buying a new GM car.

Although this strategy benefited GM in the first instance, the rest of the competitors, such as Ford, could replicate the same tactic ending in a better position.

What is remarkable here is how the relationship among competitors, traditionally seen as a win-lose proposition, can be different from one and even be changed. Moreover, how cooperation can be a better strategy for all.

Looking for win-win strategies has several advantages:

- It is not a common practice, so there might be more opportunities

- As it is a winning result for competitors, they will not fight against them

- There will not be retaliation from the other incumbents

What is “Value Net”?

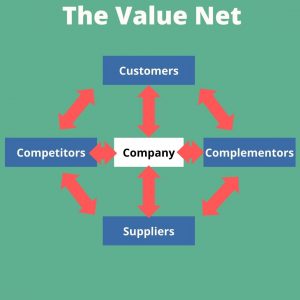

In order to make these kinds of analyses, first, we need to identify and categorize the different players in each environment.

For that, the authors of this book introduce the concept of Value Net, a schematic map in which we can see the interdependencies among the different players.

The Value Net Model Elements and their interdependences

As we can see, these interdependencies can be horizontal (with substitutors and complementors) but also vertical (with customers and suppliers).

What are the elements of the game? (PARTS)

After drawing the Value Net of a business, we need to identify the elements of the game. According to the game theory, there are five (PARTS):

- Players

- Added values

- Rules

- Tactics

- Scope

We require all of them to describe any interaction. Moreover, we need to change at least one of these elements to change the game.

Changing the Players

As an example of how the introduction of a new Player changes the existing game, Branderbunger and Nalebuff describe how Holland Sweetener Company disturbed the NutraSweet relationship with Coke and Pepsi.

Being a kind of monopoly protected by a patent, NutraSweet, a Monsanto brand, enjoyed a high-profit margin in its sales to Coke and Pepsi.

The introduction of HSC in Europe, once the patent expired, at a lower price forced Monsanto to lower its margins, but it remained the unique vendor signing long-term contracts with these two customers.

HSC added value to Coca-Cola and Pepsi just with the threat of entering. HSC did not benefit from it, but they could have done it had they asked for some compensation in advance from these customers. A similar example of this strategy is explained in the case of the cellular phone business in 1989.

Cheap Complements

Another way of adding value for a company could be forcing a decrease in the prices of complements.

Hardware is the classic complement to software. The authors bring the case of 3DO, which owns a 32-bit CD-ROM hardware-and-software technology for next-generation video games.

In order to drive down the price of the hardware, they gave away the license to produce the hardware technology, making the hardware a commodity.

Creating competition in the complements market is the flip side of coopetition. It is a win-lose proposition with complementors, while traditionally, we think of them as only win-win interactions.

Changing the added values

There are two options for improving our position. Either to raise our own added value or to lower that of others.

Here they describe the case of Trans World Airlines when they introduced the Comfort Class in 1993. Apart from raising the prices of these seats, propagating this change among the other competitors, they managed to reduce the offer, increasing their added value.

Less intuitive is the strategy of lowering the added value of others. For that, they bring a game that Adam played with his 26 MBA students. Adam has 26 black cards, and each of the students has one red card. Any couple of black-red cards gets a $100 prize. Intuitively, it seems fair to think that players will bargain their cards for $50 each. However, in order to lower the value of his competitors, the students, Adam could burn in public display three of his black cards. In this case, there will be three students that are not going to get anything, so their value has been lowered, and now Adam could negotiate a much better deal with them.

As a real case, they describe the case of Nintendo bargaining with its major retailers. Underserving the demand lowered their bargaining power, allowing Nintendo to get better deals.

Pumping up profits

They also introduce a case in which the added value was protected. In 1970 the CEO Minnetonka had the idea of Softsoap, a liquid soap that a pump would dispense. As there was no way to protect this idea against its competitors (nothing of the product could be patented), he came up with the idea of locking up all the production of the most complicated part to manufacture of the pump. With this strategy, it could enjoy some time of profits before its competitors could enter the market.

Changing the rules

One way in which new competitors can limit the retaliation of incumbents is by maintaining a low market share. Being aware of this possibility is essential, as a price war would not benefit any of them.

Kiwi International Air Lines understood these ideas in 1992. In the words of his CEO: “we designed our system to stay out of the way of large carriers and to make sure they understand that we pose no threat. … Kiwi intends to capture, at most, only 10% of the share of any one market.”

Meet-Competition-Clause (MCC)

Another rule used in some industries, such as the one of carbon dioxide, gives the incumbent seller to make the last bid.

This rule can assure long relationships between customer-provider but at the same time discourages the entry of new competitors.

“Players who live in glass houses are unlikely to throw stones. So you should be pleased when others build glass houses.

Changing perceptions

Another way of changing the game could be only clarifying what could happen or, in some cases, the reverse, trying to hide the consequences.

To reflect these possibilities in actual cases, the authors bring one example of a newspapers competition in 1994 and another of an investment bank.

Changing the scope

As an example of managing the scope to change the game, they describe how Nintendo refused to compete with Sega in its new 16-bit console while enjoying good profits with its 8-bit one.

The traps of strategy

Finally, they talk about what can hold us from changing a game:

- To think you have to accept the game you find yourself in

- To think that changing the game must come at the expense of others

- To believe that you have to find something to do that others can’t

- To fail to see the whole game

- To fail to think methodically about changing the game